One Pig Live

- Categories Music, Performance

I was very lucky to meet musican, producer, and composer Matthew Herbert in 2011 and learn about his exciting One Pig project. For this album Matthew recorded a single pig’s life “from birth to plate” and constructed an album out of the resultant sounds.

He commissioned me to create a brand new controller/instrument built especially for the show – the StyHarp. As the name suggests, the StyHarp is designed to mimic a pig sty, and is used in the show to trigger, control, and effect sounds in real time by pulling, plucking, and twisting the strings. It’s a very physical thing to play, which is part of the fun. I don’t have any great video footage of it in action, so you’ll have to make do with this hilarious video of me jamming with the band during rehearsals:

Our first show was in London, at the Royal Opera House as part of the Deloitte Ignite Festival. A small sampling of the venues we have played since:

Liquid Room, Tokyo

Berghain, Berlin

Cafe Oto, London

Queen Elizabeth Hall, London

Palais de Tokyo, Paris

RCNM, Manchester

Casa da Musica, Porto

Ancienne Belgique, Belgium

And many many more. Here’s a trailer for one segment of the tour:

and here’s a little video Reuter’s made before one of our London shows:

You can read a review of one of our shows in The Guardian, among many other places.

When Matthew and I first started thinking about what we wanted to make for his show, we were certain that we wanted something physical, something with resistance and response, something that looked strange, perhaps even frightening, and evoked the themes present in the One Pig album. We wanted to be able to have direct control over sound, but also wanted something with a life of its own. The musicality and the theatrics had to be on equal footing. All of these things led me to want to make something with strings, something big and something that would take effort to play.

The main component of the StyHarp is the string sensors, which are ripped from Gametrak controllers. These gadgets are a sort of proto-Kinect, designed for PCs and game consoles. They were marketed as 3D motion trackers, and packaged mostly with golf games (with comical miniature golf clubs) and sold only in the UK from 2000-2006 or so. To use a Gametrak the player wears a pair of gloves which are connected to a base station with some wire (which looks suspiciously like orange fishing line). Inside the base station these two lines each go into a spool, which is connected by a few gears to a standard potentiometer. The potentiometer thus turns as the wire is pulled in and out. The wire is also fed through an X-Y joystick-style potentiometer. The result is that the distance and location relative to the base station can be tracked with startling accuracy, all using technology that has been around for over a hundred years. Pretty great, huh? It’s a wonder no one thought of designing a controller like this for the Atari or the Binatone TV Master.

Many thanks to Jung In Jung and Martin Parker for introducing me to the Gametrak and for helping me track down a few extra for this project!

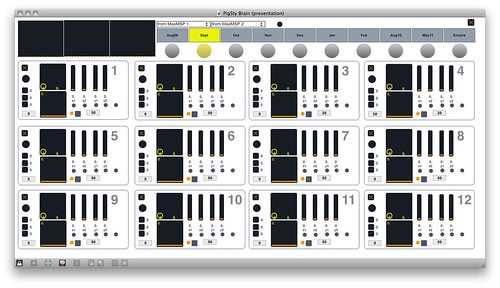

So the design we settled on for the StyHarp called for 12 Gametrak strings (four per side, three sides), thus six Gametraks. Each Gametrak has a USB output, but it turns out that only the XBox and PC versions of the Gametrak can be used as a HI Device (and the XBox version requires a little hacking even to do that), so it quickly became apparent that I would not be able to just plug them all into my computer. However, Jon (aka Lucky Frame partner in crime) suggested I tap into the outputs directly from the potentiometers, and plug them into an Arduino, thus bypassing the Gametrak’s USB circuitry altogether. That worked great! However….each Gametrak has six parameters (x, y, and distance for each), which means I needed 36 analog inputs, and the Arduino only supports 6. Even the Arduino Mega only supports 16! So I decided to use the Arduino Mux Shield from Mayhew Labs. This lets me have up to 48 analog inputs, which are multiplexed through the digital pins in some way that I don’t understand.

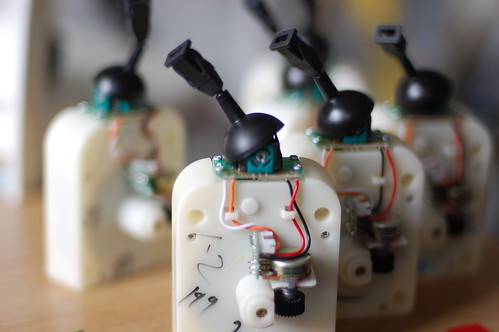

During the early stages of development I was planning on using the Gametraks in a fairly un-hacked form. This was because the models that I had bought did not seem all that conducive to hacking – the gearing was more or less separated from the wire spools, and it seemed like a headache. Some people have done it (including this guy, who used it to build a Gametrak-based Ondes Martenot), but it didn’t seem worth it to me. However, I ended up finding a few later model Gametraks, apparently released in 2006, which use a slightly different construction which lends itself to hacking – in fact, the whole reel, gearing, and potentiometer setup is tightly packaged into individual and completely separate little boxes! It’s amazing. So I found a bunch of these and ripped them apart, and I had all the sensors I needed. I was even able to hack out the little connector wires that they use. If this interests you, be sure to find the ones that have rounded ends like this.

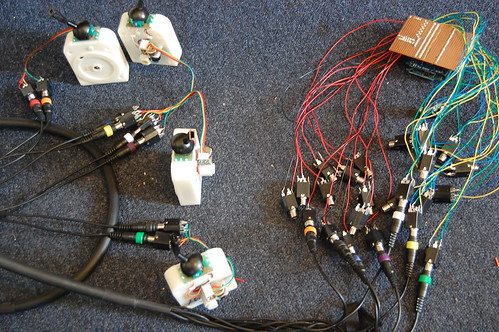

To connect everything to the Arduino I’m using 1/4″ stereo jack cables. This is partially because I had a loom kicking about my studio, but also because it is an affordable and robust connector, and venues are generally guaranteed to have a bunch of them just in case. I therefore attached two female connectors to each set of wires which connect to the Gametrak sensors, and I built a patchbay box for my Arduino.

On the software end, the Arduino is communicating through USB using a serial data system built by Jon in Processing. This is much more robust than the software provided by Mayhew Labs, which kept on crashing because of the load of data coming through…Jon implemented a brilliant call-response system which eliminated all crashing. Go go Lucky Frame! So Jon’s utility is sending all the data via OSC into Max/MSP, where I’ve built a flexible patch for sending MIDI notes and controls to Ableton Live, where all of the sound processing and triggering is going on. The sounds are all original recordings from the One Pig album, and they are triggered by pulling or plucking the strings. Twisting and pulling the strings then control other effects like delays, filters, and so on.

The Gametraks are all connected to stands using plumbing fixtures, and the strings are pulled out to connect across and create the fence. I am inside for much of the show, and the rest of the band joins me at one point.